|

Robert Clark: a true Carlton hero

In his book Play!, a history of Carlton from its inception until the Second World War, long time club skipper Dr N.L. Stevenson, recorded the arrival at Carlton of a young graduate from Aberdeen University: “R.S. Clark came to us from Aberdeenshire with a great cricket reputation. He was a beautiful bat, using his wrists to full advantage in making a panoply of classic strokes.” But it was not the quality of his batting that made Clark a celebrity during the early part of the Twentieth Century; rather it was his role in one of the most remarkable survival stories of all time ...

Clark’s Carlton career was interrupted the following year when he took up the post of naturalist in charge of fishery investigations at the Plymouth Marine Biological Association. At the same time, legendary Antarctic explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton was planning a hugely ambitious expedition from Plymouth. Shackleton’s aim was to cross the continent from sea to sea, via the pole. In 1914 Shackleton invited Clark to join the expedition as biologist – an offer that the batsman at first refused. However, legend has it that a last minute change of heart saw Clark jump onto the Endurance from the pierhead just half an hour before the ship departed. Even then he appears to have remained in two minds, writing in his diary not long after departure: “I cannot think what I am doing here and shall certainly return from Buenos Aries.” Before long though, Clark was committed to the cause and quickly turned his energies to logging observations and collecting specimens. He was apparently fascinated by the icy seas and landscapes and, as the Endurance made its way through the polar ice pack, he and his shipmates took delight in interpreting the ‘Claak Claak’ of the penguins as a sign that the penguins were calling out to the Carlton man. As the Endurance sailed further into the Weddell Sea, the conditions became steadily worse and by early 1915, the ship had become completely trapped in an ice floe. Shackleton quickly realised that there would be no escape until spring and the crew set to work to turn the ship into an ice station. Clark and his colleague took possession of a temporary cubicle, which they set up as their living quarters, christening it “Auld Reekie”.

By September of 1915, the moving and breaking of ice caused by the arrival of Spring began to exert great pressure on the ship's hull and, on 24th October, the water began to pour in. Shackleton soon had no option but to order the abandonment of the Endurance and the men set up camp on a nearby ice floe. On 21st November the wreck finally disappeared below the surface (right), taking all Clark’s collections and records to the bottom of the ocean. Despite being apparently perceived as the archetypal dour Scotsman, Clark was a popular colleague and his calm outlook helped to steady morale in the hard months spent on the ice. For four months Shackleton and his group hoped that the ice floe would drift in the direction of land. However, when the floe finally broke in two in April of 1916, Shackleton ordered the crew into lifeboats to head for the nearest land. After five days the three boats reached Elephant Island, an inhospitable icebound isle almost 600 miles south of the Falkland Islands.

Marooned far from the nearest shipping lane, Shackleton calculated that the only hope of survival was to take one of the open boats to the South Georgia whaling stations, almost 800 miles away, to summon help. Clark was left on Elephant Island with 21 of his shipmates and the remaining two boats were turned upside down to create a hut. According to a later report Clark “was allotted a berth in the "attic" between the thwarts and the boat bottom which required him to stow his long body horizontally, and where he was compelled to sleep, read and eat in the same position.” He apparently turned out to be something of a creative cook, making best use of the staple diet of penguins, seals, limpets and seaweed. Miraculously, Shackleton reached help after a two week sea journey and a 36 hour trek on foot across South Georgia. For Clark and his colleagues, rescue was still a long way away though and it was only after three failed attempts to break through the ice fields that Shackleton finally reached Elephant Island on 30th August of 1916. Following his rescue, Clark became an officer in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, serving his time on minesweeping duties. After the end of the war, he returned to the Marine Biological Laboratory at Plymouth before heading back to his native Aberdeenshire to become the senior naturalist at the Marine Research Laboratory at Torry. Despite working in Aberdeen, Clark’s feelings for Carlton clearly remained very strong and he regularly made the journey south to play for the club. In 1922 he finished third in the club’s batting averages and, two years later, he was a member of the Carlton side that went through the 1924 season undefeated. That year Clark made three further appearances for Scotland, scoring 29 against the touring South Africans.

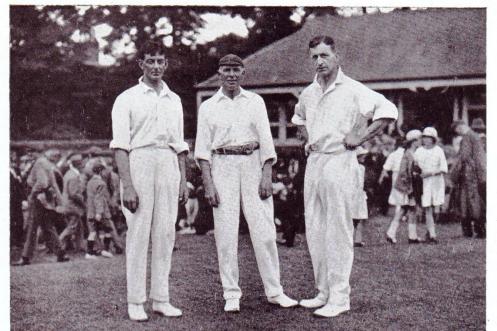

Clark (back row, first left) and his 1922 Carlton team-mates. Dr Stevenson was always keen to attract top players to Grange Loan for matches that would draw big crowds (and therefore boost income) and in 1924, following the appearance of Sydney Barnes for Carlton in 1922 and 1923, he tempted Australian test bowler EA (Ted) McDonald, who had taken 27 wickets at 24 in the Ashes series in England just three years before, to turn out for Carlton in a match against J.W.H.T. Douglas's Essex XI. A pre-match photograph (below) shows Stevenson standing in front of the old Grange Loan pavilion, flanked by his two celebrity team-mates: the great fast bowler on his right and the Antarctic hero on his left.

In 1925 Clark gained a D.Sc. (Doctor of Science) and took over as director of the Fisheries Research Laboratory in Aberdeen. He retired in 1948 and died two years later at the age of 68. While Robert Selbie Clark will always be renowned for his part in one of the greatest ever polar adventures, it was his batting that moved his Carlton skipper to deliver a glowing verdict: "On his day he gave the impression of being a super-batsman, so effortless was his play, which even to-day is spoken of with admiration from Mannofield to the playing fields of far-off Devon, where as an opening batsman he scored several centuries and, in at least one season, headed the Devon county batting averages. In my time the Club has had few better recruits than Dr R.S. Clark." |

Robert Selbie Clark, a graduate of Aberdeen University, arrived in Edinburgh in 1911 to take up a position as zoologist at the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory. Like so many discerning ‘incomers’ to the city before and since, Clark found his cricketing home at Grange Loan. His on-field impact was immediate and he made his Scotland debut in 1912 against Ireland in Dublin.

Robert Selbie Clark, a graduate of Aberdeen University, arrived in Edinburgh in 1911 to take up a position as zoologist at the Scottish Oceanographical Laboratory. Like so many discerning ‘incomers’ to the city before and since, Clark found his cricketing home at Grange Loan. His on-field impact was immediate and he made his Scotland debut in 1912 against Ireland in Dublin. Despite their predicament, Clark assiduously continued his biological work. At one point a colleague reported hearing a great yell from the ice floe and found Clark “dancing about and shouting Scottish war-cries. He had secured his first complete specimen of an Antarctic fish, apparently a new species.”

Despite their predicament, Clark assiduously continued his biological work. At one point a colleague reported hearing a great yell from the ice floe and found Clark “dancing about and shouting Scottish war-cries. He had secured his first complete specimen of an Antarctic fish, apparently a new species.”